Many years ago, at an author event, someone in the audience asked me, “If you could write like anyone, who would it be?” At the time, I had finally clawed my way out of the unpublished writer’s corner and was still finding my own writer’s voice. The answer to the question was obvious: Like myself, of course. I wanted to write like the best darned Kate Flora that I could.

Two decades, and twenty-one books later, I know that there are many, many answers to  that question. The library is full of authors whose work has magical aspects I would like to have. Of course I would like to write like John Steinbeck, the only writer ever who, after I read Cannery Row, left me writing in his style for a week or two. I would love to write his characters and his hooptedoodle chapters and just generally be able to convey his evident deep fondness for his characters. In his ten rules for writers, Elmore Leonard says this about Steinbeck:

that question. The library is full of authors whose work has magical aspects I would like to have. Of course I would like to write like John Steinbeck, the only writer ever who, after I read Cannery Row, left me writing in his style for a week or two. I would love to write his characters and his hooptedoodle chapters and just generally be able to convey his evident deep fondness for his characters. In his ten rules for writers, Elmore Leonard says this about Steinbeck:

What Steinbeck did in ”Sweet Thursday” was title his chapters as an indication, though obscure, of what they cover. ”Whom the Gods Love They Drive Nuts” is one, ”Lousy Wednesday” another. The third chapter is titled ”Hooptedoodle 1” and the 38th chapter ”Hooptedoodle 2” as warnings to the reader, as if Steinbeck is saying: ”Here’s where you’ll see me taking flights of fancy with my writing, and it won’t get in the way of the story. Skip them if you want.”

And speaking of Elmore Leonard, who wouldn’t like to write like him, with brilliant dialogue and ways of conveying characters almost entirely through their actions. When I teach, I always read my students Leonard’s Ten Rules for Writers, https://www.nytimes.com/2001/07/16/arts/writers-writing-easy-adverbs-exclamation-points-especially-hooptedoodle.html, and then tell them that they can break any of these rules if they

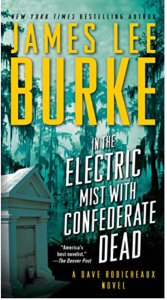

Writing well enough if, of course, the key. Most of us would love to be able to write like James Lee Burke, who can pull off a ghost story in the midst of a compelling contemporary mystery story in In the Electric Mist with Confederate Dead. An opening like this can make you glad he disregarded the advice to never open a book with the weather:

Writing well enough if, of course, the key. Most of us would love to be able to write like James Lee Burke, who can pull off a ghost story in the midst of a compelling contemporary mystery story in In the Electric Mist with Confederate Dead. An opening like this can make you glad he disregarded the advice to never open a book with the weather:

The sky had gone black at sunset, and the storm had churned inland from the Gulf and drenched New Iberia and littered East Main with leaves and tree branches from the long canopy of oaks that covered the street from the old brick post office to the drawbridge over Bayou Teche at the end of town. The air was cool now, laced with light rain, heavy with the fecund smell of wet humus, night-blooming jasmine, roses, and new bamboo. I was about to stop my truck at Del’s and pick up three crawfish dinners to go when a lavender Cadillac fishtailed out of a side street, caromed off a curb, bounced a hubcap up on a sidewalk, and left long serpentine lines of tire prints through the glazed potholes of yellow light from the street lamps.

Go ahead and match that!

This week, I am a prepping to write a short story, due way too soon, that must take a presidential election in a different direction from the way it went. Having decided that Huey Long will be my character, I am immersed in a reread of Robert Penn Warren’s All the King’s Men. I do not want to start writing like Warren, but I am definitely caught up in his long, deep descriptions of almost everything. At this point in the book (early!) our narrator, Burden, is following an early Willie Stark campaign. He is lying on his bed, listening to Stark pace the follow in the room next door, described thus:

I’d be lying there in the hole in the middle of my bed where the springs had given down with the weight of wayfaring humanity, lying there on my back with my clothes on and looking up at the ceiling and watching the cigarette smoke flow up slow and splash against the ceiling like the upside-down slow-motion moving picture of the ghost of a waterfall or like the pale uncertain spirit rising up out of your mouth on the last exhalation, the way the Egyptians figured it, to leave the horizontal tenement of clay in its ill-fitting pants and vest.

Whew! I’m impressed but boy is it slow going, and there are 600 pages in the book. As I read, I wonder what Elmore Leonard would have to say about the book. I’m also loving the slow, stately pace of the writing and wondering how a crime scene would feel if I imported some of Warren’s style.

So since I have to get back to my homework, I leave you with this question. Whose writing impresses you? Knocks your socks off? Makes you catch your breath? Makes you want to copy out paragraphs in a notebook to save for future reference?

Happy reading!

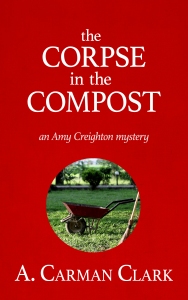

mother, A. Carman Clark, published her first mystery, The Maine Mulch Murder, featuring 60-something freelance editor and gardener Amy Creighton, when she was 83.

mother, A. Carman Clark, published her first mystery, The Maine Mulch Murder, featuring 60-something freelance editor and gardener Amy Creighton, when she was 83.  Two summer ago, in the space between my own books, and nudged by Ann and Paula at the Mainely Murders bookstore

Two summer ago, in the space between my own books, and nudged by Ann and Paula at the Mainely Murders bookstore

many times that my Malden Man collection has disappeared. Among those lost clippings were some that proved the point about Boston’s provincial papers, including “Malden Man Found Alive in Grand Canyon” and a charming story reporting that Malden Man had been injured by a falling chimney during a Los Angeles earthquake. Despite that missing file, I still have a sheet of paper on which I have recorded some of the poor fellow’s ups and downs. Malden Man, it seems, does not have a very good character. Over the years, he’s had a steady stream of run-ins with the law. The Boston Strangler, Albert De Salvo, was a Malden Man. While out hunting, Malden Man shot at what he thought was a turkey and accidentally hit a father and a son who were also hunting. He’s been convicted for illegally importing elephant ivory. And perhaps most dreadful of all, a Boston news source reports:

many times that my Malden Man collection has disappeared. Among those lost clippings were some that proved the point about Boston’s provincial papers, including “Malden Man Found Alive in Grand Canyon” and a charming story reporting that Malden Man had been injured by a falling chimney during a Los Angeles earthquake. Despite that missing file, I still have a sheet of paper on which I have recorded some of the poor fellow’s ups and downs. Malden Man, it seems, does not have a very good character. Over the years, he’s had a steady stream of run-ins with the law. The Boston Strangler, Albert De Salvo, was a Malden Man. While out hunting, Malden Man shot at what he thought was a turkey and accidentally hit a father and a son who were also hunting. He’s been convicted for illegally importing elephant ivory. And perhaps most dreadful of all, a Boston news source reports:

Shall Lead Them, I’ve been finished a project I started last summer–retyping, and editing, the mystery my late mother, A. Carman Clark, was working on when she died. The Corpse in the Compost sat in the corner of my office, guilt-tripping me, for years, but I never had time to settle in and work on it. Last summer, I decided the time had come. For two months, when I could, I reread the work, the comments I’d given her years ago, and comments from her close friends. I began to edit, scribbling, as one does on hard copy, all over the pages, along the margins and on the back.

Shall Lead Them, I’ve been finished a project I started last summer–retyping, and editing, the mystery my late mother, A. Carman Clark, was working on when she died. The Corpse in the Compost sat in the corner of my office, guilt-tripping me, for years, but I never had time to settle in and work on it. Last summer, I decided the time had come. For two months, when I could, I reread the work, the comments I’d given her years ago, and comments from her close friends. I began to edit, scribbling, as one does on hard copy, all over the pages, along the margins and on the back. I don’t have a story idea for a new Thea, although a new Burgess is beginning to percolate. My editor suggested I might consider starting a new series, so I began looking in the filing cabinet, wondering if one of the many “books in the drawer” might become a new series. I knew that I’d written one book in my architect series, and started another, but no matter where I looked, Bones are Bad for Business was nowhere to be found. I searched the cupboards. I looked in the basement. I looked in old filing boxes. Finally, on my hands and knees, I moved some stacks of books on my office floor and there, tucked under a bookcase, was the manuscript.

I don’t have a story idea for a new Thea, although a new Burgess is beginning to percolate. My editor suggested I might consider starting a new series, so I began looking in the filing cabinet, wondering if one of the many “books in the drawer” might become a new series. I knew that I’d written one book in my architect series, and started another, but no matter where I looked, Bones are Bad for Business was nowhere to be found. I searched the cupboards. I looked in the basement. I looked in old filing boxes. Finally, on my hands and knees, I moved some stacks of books on my office floor and there, tucked under a bookcase, was the manuscript. job and stay home for a few years with my boys. I immediately had the terrified thought, But I’ve always worked. Now what will I do? Then I thought, I’ve always wanted to write. Maybe it is something I can do while the boys nap. Naive thought. My boys were not nappers. It was hard to find those spaces where it was quiet enough to write. But I started a novel, and it sent me on the course I am still on today.

job and stay home for a few years with my boys. I immediately had the terrified thought, But I’ve always worked. Now what will I do? Then I thought, I’ve always wanted to write. Maybe it is something I can do while the boys nap. Naive thought. My boys were not nappers. It was hard to find those spaces where it was quiet enough to write. But I started a novel, and it sent me on the course I am still on today. about yummy things to make the holiday brighter or suggestions for clever décor that sets off a stunning table for an afternoon and for which storage space must be found the other 364 days of the year. Now that the last platter is washed and put away, the wine glasses are back in their boxes and I’ve made refrigerator space for the tattered remnants of a twenty pound turkey, I’m thinking beyond my overfull stomach and my uncomfortably tight pants to the new challenge of making holidays pleasing and memorable as the cast of characters around the table changes.

about yummy things to make the holiday brighter or suggestions for clever décor that sets off a stunning table for an afternoon and for which storage space must be found the other 364 days of the year. Now that the last platter is washed and put away, the wine glasses are back in their boxes and I’ve made refrigerator space for the tattered remnants of a twenty pound turkey, I’m thinking beyond my overfull stomach and my uncomfortably tight pants to the new challenge of making holidays pleasing and memorable as the cast of characters around the table changes. This year we did a family dinner again, a wonderful event that let me see the family being reconfigured as the children become adults with interesting lives. My niece who is in her first year of teaching talked for hours about the challenges of a difficult third grade and her strategies for managing. She described her fondness for her students, even the ones who can’t sit still and never stop talking. She talked about her exhaustion and the huge amount of prep. Unspoken behind the story was how much she wished her grandmother, who had been a genuinely great teacher, was there to listen and to offer unconditional love and advice.

This year we did a family dinner again, a wonderful event that let me see the family being reconfigured as the children become adults with interesting lives. My niece who is in her first year of teaching talked for hours about the challenges of a difficult third grade and her strategies for managing. She described her fondness for her students, even the ones who can’t sit still and never stop talking. She talked about her exhaustion and the huge amount of prep. Unspoken behind the story was how much she wished her grandmother, who had been a genuinely great teacher, was there to listen and to offer unconditional love and advice.